Hey there! I’m Emma, your American Accent Coach. Today we’re diving into a sound that seems easy… but can cause some surprisingly tricky problems for English learners: the American V sound.

If your native language doesn’t have this sound—or if it’s pronounced differently—you might find yourself saying “berry” instead of “very”, or “safe” instead of “save”. And trust me, you’re not alone—this is one of the most common pronunciation challenges I see with my students.

In this guide, we’ll go step-by-step through:

By the end, you’ll have not just the theory, but the muscle memory to make /v/ sound natural and confident in your speech.

The American /v/ is what linguists call a voiced labiodental fricative. That’s a fancy way of saying:

Think of it as a mix between a hum (from your throat) and a gentle air hiss (from your lip and teeth).

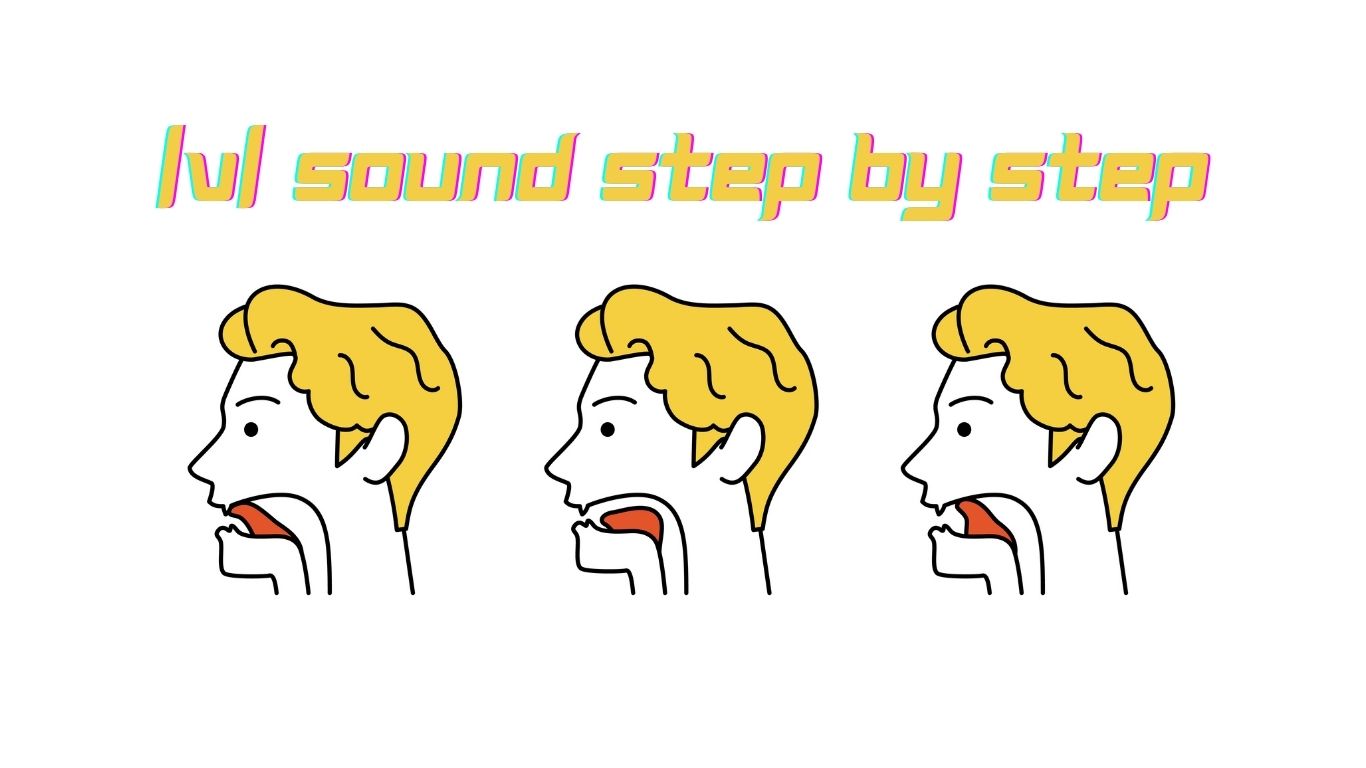

Here’s my “coaching session” breakdown:

1️⃣ Jaw Position

Keep your jaw relaxed and slightly closed—close enough that your lower lip can comfortably reach your upper teeth.

2️⃣ Lip + Teeth Contact

Lightly touch the inside edge of your bottom lip to the bottom edge of your top front teeth. No biting! Just gentle contact.

3️⃣ Airflow

Push a smooth, steady stream of air between the teeth and lip.

4️⃣ Add Your Voice

Turn on your vocal cords. That’s the difference between /f/ and /v/.

Coach’s Tip: If you can say /f/ correctly, you can make /v/ by keeping the exact same mouth position and simply adding voice.

✨ Quick Mirror Drill

This builds instant awareness of the voicing difference.

Even though V sound is short and simple in writing, it’s easy to slip up when speaking—especially if your first language doesn’t have this sound or uses it differently.

Here are the three biggest trouble spots I hear from learners—and exactly how to fix them.

❌ The mistake: You stop vibrating your vocal cords, and your /v/ turns into /f/.

Example: “I lof you” instead of “I love you.”

Why it happens:

Some languages (like German, Dutch, Russian) naturally drop voicing at the end of words—so “love” may sound like “luff.”

✅ Fix it:

❌ The mistake: You bite your lip too firmly or curl it way under your teeth. This can make your /v/ sound tight, distorted, or even painful.

Why it happens:

Learners often think “strong sound = strong pressure,” but for /v/, less is more. It’s about precision, not force.

✅ Fix it:

❌ The mistake:

Why it happens:

✅ Fix it:

✨ Pro Tip: If you’re not sure you’re getting it right, start from /f/ and “turn on” your voice—that will put you in the correct /v/ position.

Quick Self-Check Exercise

One of the fastest ways to improve your /v/ is to practice it against sounds that are almost the same.

We call these minimal pairs—two words that differ by just one sound.

Think: van vs. fan, vest vs. west, vote vs. boat.

These small differences matter a lot—mix them up and you might say something completely different than you mean.

These two are “sister sounds” because they’re made in exactly the same spot (bottom lip + top teeth) and in the same way (air flowing through a narrow gap).

The only difference? /v/ is voiced, /f/ is voiceless.

Think of /v/ as “f with vibration.”

How to feel it:

Minimal Pair Practice:

Pro Tip: In American English, the vowel before /v/ is usually a little longer than before /f/. Compare safe vs. save—you’ll hear the difference.

Both /v/ and /w/ are voiced and use the lips, but they look and feel completely different:

| Feature | /v/ | /w/ |

| Lip position | Bottom lip touches top teeth | Lips rounded forward |

| Airflow | Friction (hissing + buzz) | Smooth glide into vowel |

| Teeth contact | Yes | No |

How to test it:

Minimal Pair Practice:

These two are both voiced, but the manner is different:

Also, /b/ uses both lips together, while /v/ uses teeth + lip.

Minimal Pair Practice:

Drill: The Three-Way Challenge

Say these out loud, slowly at first:

This will train your lips, teeth, and voice to move quickly between sounds without mixing them up.

Once you can say the v sound clearly, the next step is knowing how it shows up in writing.

Luckily, /v/ is one of the more predictable English sounds—but there are a few special rules and exceptions every learner should know.

In most cases, /v/ is simply written with the letter v:

In English, words almost never end with just the letter v.

Instead, we add a silent e at the end.

That’s why we write:

This is just a spelling rule—it doesn’t change the pronunciation. The /v/ stays the same.

You’ll almost never see vv in standard English spelling.

A few informal or modern words do have it (savvy, divvy), but it’s rare.

Ever wonder why we spell love, glove, and above with an o instead of a u?

It’s a historical handwriting rule from centuries ago—scribes avoided writing too many letters with vertical lines together (like u, v, n, m) because it made words hard to read.

So, in words like love or cover, the o replaced u for visual clarity.

The little word of is special—it’s spelled with f but pronounced with /v/: /əv/.

Compare:

You just have to memorize this one—it’s one of the most common words in English.

✨ Quick Spelling Practice

Fill in the blanks with the correct spelling:

Here’s some good news: once you master the /v/ sound, you can use it anywhere in the United States and be understood perfectly. Unlike some vowel sounds that change depending on the region (like “cot” vs. “caught”), /v/ is stable and consistent across all American accents.

So whether you’re in New York, Texas, or California, your /v/ will sound the same to native speakers. ????

When you invest time in practicing /v/, you’re building a skill that doesn’t need “regional adjustments.” You won’t have to relearn it for different parts of the country—one clear, correct /v/ works everywhere.

Even though the sound itself is stable, you might notice a slightly different version in certain fast or connected speech situations. Here’s the main one:

Don’t worry—you don’t need to practice this variation. It happens automatically for native speakers, and your standard /v/ will sound just fine.

Some English learners worry that Americans might mix up /v/ with /w/ or /b/—but that only happens for learners, not native speakers.

If you clearly pronounce /v/ with teeth on lip + voice, Americans will instantly recognize it.

✨ Quick Listening Drill

Listen to these pairs and focus on hearing the /v/ in different positions:

Tip: Notice that no matter the speaker’s accent, /v/ always has that buzz + light lip-teeth contact sound.

Now that you understand what /v/ is and how it works in American English, it’s time to train your mouth, ears, and brain to use it naturally.

Here’s my tried-and-true method for building strong, reliable /v/ pronunciation—whether you’re a beginner or polishing your accent.

You can’t pronounce a sound confidently if your brain can’t hear it clearly. Start with listening drills:

✨ Pro tip: Apps like ChatterFox let you practice with AI and get instant feedback, so you’ll know right away if you got it right.

Before jumping into words, make sure you can hold a clean, sustained /v/:

This “F to V” trick is one of the fastest ways to find the correct mouth position.

Once you can make /v/ by itself, practice it with different vowels:

You’ll need /v/ at the start, middle, and end of words—so practice them all:

Record yourself and compare to a native model—you’ll hear where you need to adjust.

Short phrases are the bridge between practice and real speech:

Then move to full sentences:

Say them slowly for accuracy, then faster for fluency.

The fastest way to make /v/ automatic is to use it daily:

If you’ve been struggling with /v/, you might be wondering—is it just me?

Absolutely not! Many learners from around the world have trouble with this sound, and the reasons often depend on their native language (L1).

When your brain meets a new sound, it tries to match it to something you already know. Sometimes, there’s no perfect match—so it “borrows” a similar sound, and that’s when mix-ups happen.

Here’s a breakdown of the most common /v/ challenges by language background—and how to fix them.

Why it happens:

In these languages, /v/ often doesn’t exist as a separate sound, so b and v are pronounced the same or similarly. Your mouth is used to pressing both lips together (bilabial) instead of using teeth + lip (labiodental).

Fix it:

Why it happens:

Standard Arabic doesn’t have /v/, so the closest matches are /f/ (same lip-teeth position, but voiceless) or /b/ (voiced, but both lips).

Fix it:

Why it happens:

In German, the letter w is pronounced like English /v/, so learners sometimes overcorrect and turn English /v/ into /w/.

Fix it:

Why it happens:

These languages often have /v/ but no /w/, so learners replace /w/ with /v/ in English (“vest” for “west”).

Fix it:

Why it happens:

Mandarin doesn’t have /v/, so learners may replace it with /w/ in some positions or /f/ in others.

Fix it:

Coach’s Tip: No matter your L1, combining listening drills + mirror practice + minimal pairs will fix most /v/ issues in a matter of weeks if you practice consistently.

Mastering the American /v/ sound isn’t just about one letter—it’s about clarity, confidence, and connection.

You now know how /v/ is made, how to tell it apart from similar sounds, and why it stays the same no matter where you are in the U.S.

Remember, /v/ is a high-value skill: once you get it right, it works everywhere, in every conversation. It may take time to make it automatic, but every small step—every minimal pair, every careful pronunciation—moves you closer to sounding clear and natural.

Control your /v/, and you control a key part of how you sound in English.