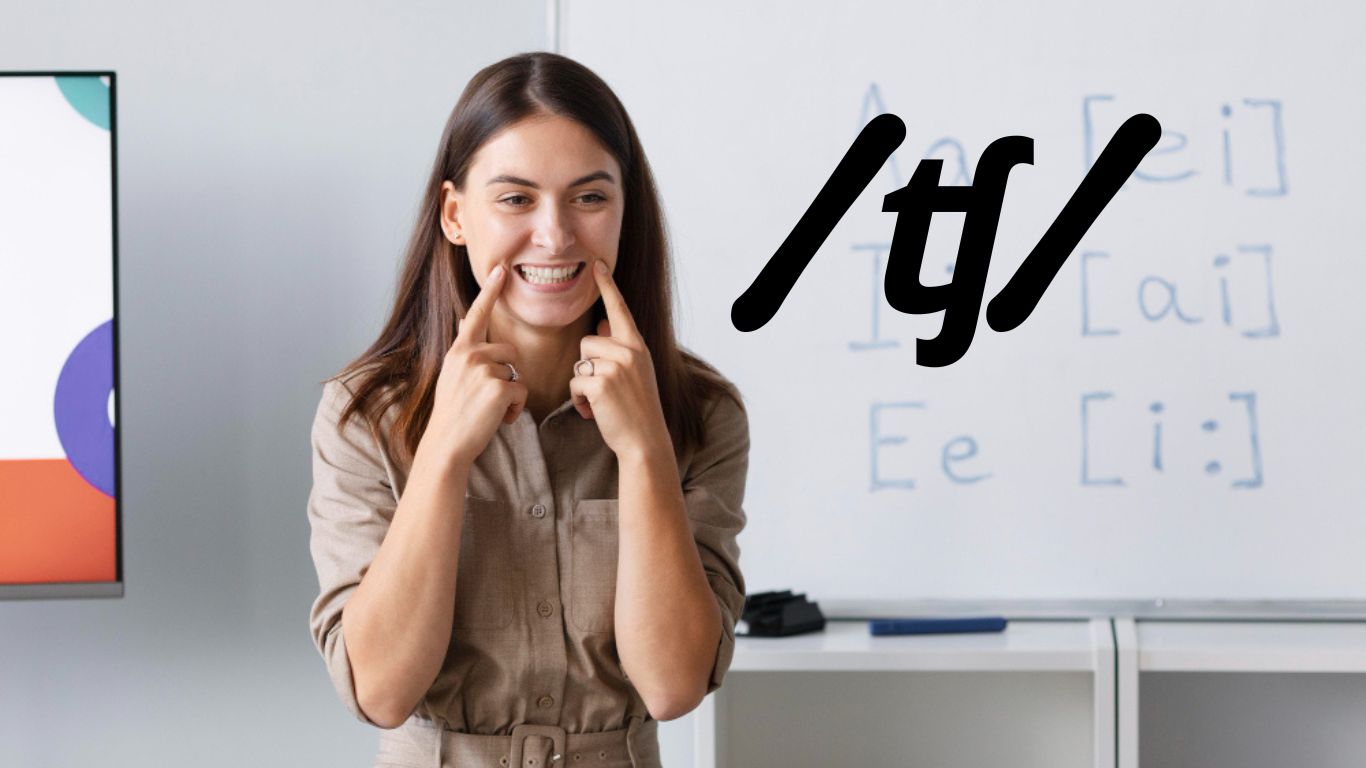

Hey there! I’m Emma, your American Accent Coach—and today we’re diving into one of those sneaky little sounds that seems simple at first… but can totally trip learners up: the American CH sound [IPA=ʧ] (that “ch” sound you hear in church, teacher, watch). If you’ve ever said shop when you meant chop, or top instead of chop, you already know how much confusion this tiny sound can cause. The good news? Once you really understand how it works, you can train your mouth and ears to get it right—and it will instantly make your English clearer and more natural.

The CH sound is special because it isn’t just one sound—it’s a blend of two: a quick stop (like /t/) plus a “sh” sound (/ʃ/). That combo can feel tricky at first, especially if your first language doesn’t have an exact match. Add to that the messy English spelling system—where “ch” sometimes sounds like /k/ (school) or /ʃ/ (chef)—and it’s no wonder learners get frustrated! But don’t worry: in this guide, I’ll break it down step by step, show you how it behaves in real speech, and give you plenty of practice ideas to help you master it.

So what exactly is this CH sound, and why does it feel so different from other consonants? In phonetics, we call it a voiceless postalveolar affricate—but don’t let the fancy name scare you off. All that means is:

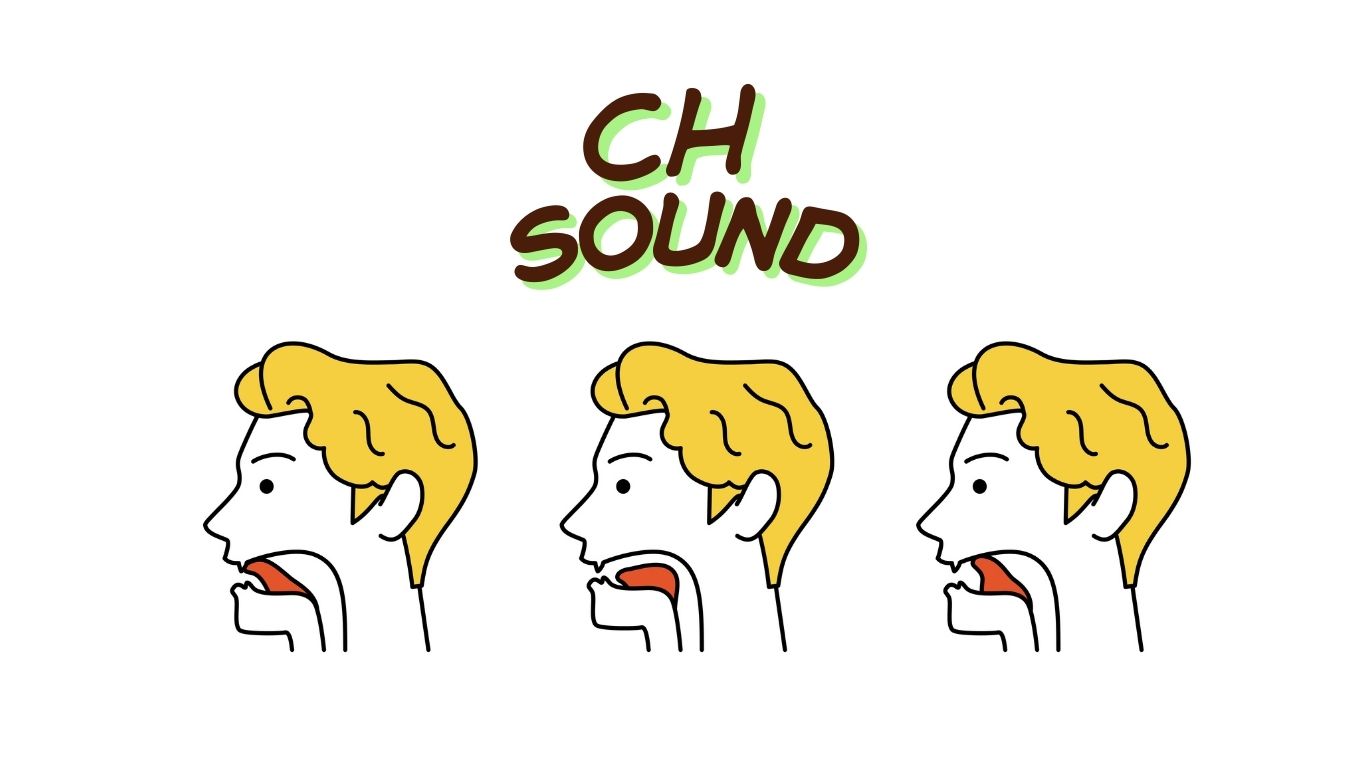

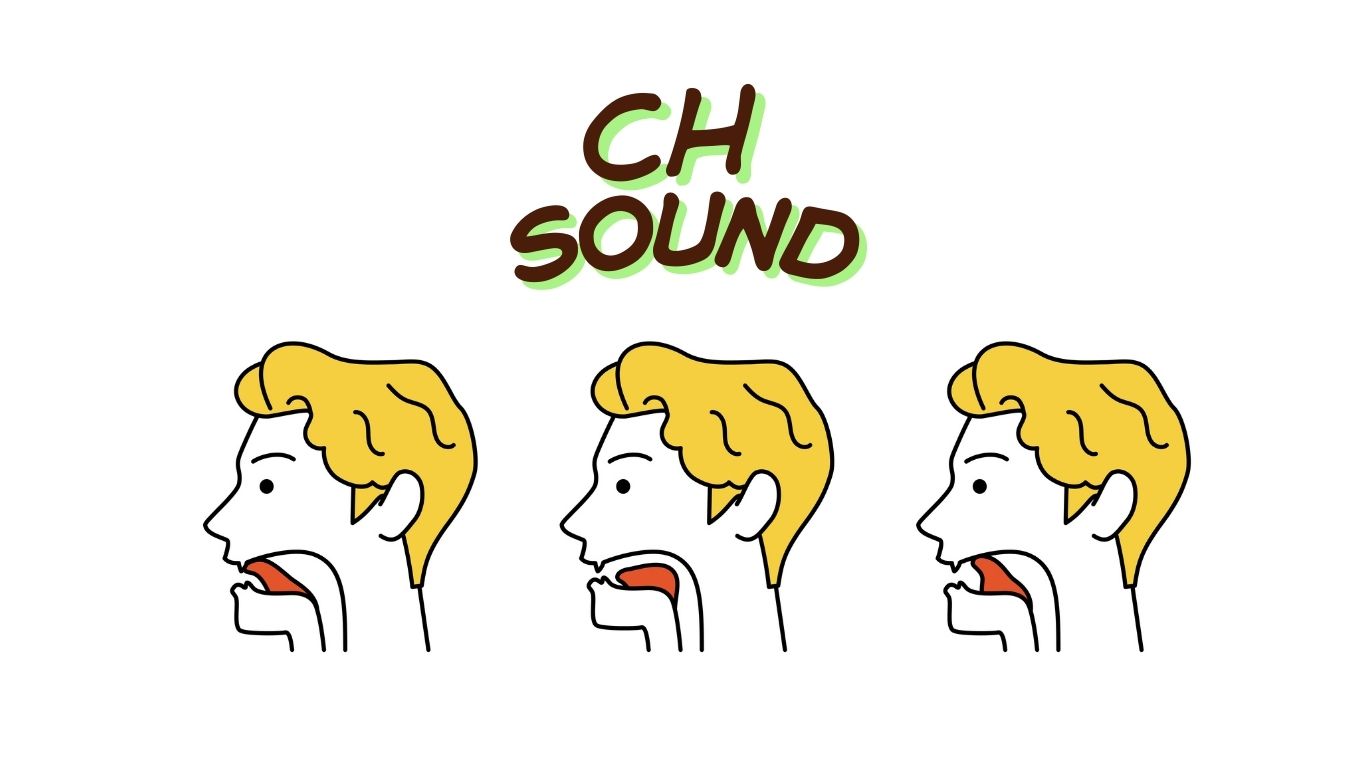

The CH sound might feel complicated at first, but when you slow it down and break it into steps, it becomes much easier. Think of it as building a little “speech recipe.” Here’s how to do it:

Practice this in small steps: first say /t/ a few times, then /ʃ/ a few times. Once those feel comfortable, blend them smoothly into /ʧ/. That’s the muscle memory you’re aiming for.

Here’s a fun fact: the /ʧ/ in church and the /dʒ/ in judge are made in exactly the same place in your mouth. Same tongue position, same lip shape, same stop-then-release movement. The only difference? Voice.

Try this quick test: put your fingers gently on your throat and say “ch, ch, ch.” Now switch to “j, j, j.” Feel that buzzing on the “j”? That’s voicing.

Why does this matter? Because if you mix them up, you can accidentally change a word’s meaning:

Once you get this contrast, you’ll avoid one of the most common pronunciation mix-ups English learners face.

If only English spelling were simple! The CH sound shows up in writing in a few different ways—and sometimes, “ch” doesn’t even mean /ʧ/ at all. Let’s break it down so you don’t have to guess every time.

This is the most common spelling for /ʧ/. You’ll see it at the beginning, middle, and end of words:

Here’s a helpful shortcut: when a short vowel (like a in cat or i in sit) comes before the final CH sound, English usually adds “tch.”

⚠️ A few exceptions break the rule: rich, which, much, such, spinach. These just need to be memorized.

Sometimes the letter t magically turns into /ʧ/. This happens when t comes before a “u” sound, especially in endings like -ture or -tual:

So if you ever see ture or tual, you can bet there’s a “ch” sound hiding inside.

Here’s the frustrating part: the letters “ch” don’t always equal /ʧ/. Sometimes they sound like /k/, sometimes like /ʃ/, and sometimes… they’re even silent! But there’s actually a bit of logic behind it, and knowing the patterns will save you a lot of guesswork.

When English borrowed words from Greek, the “ch” usually kept a hard /k/ sound. You’ll hear this in lots of scientific, academic, or technical terms:

So if the word looks a little “scientific” or formal, there’s a good chance that “ch” = /k/.

Later, English borrowed tons of words from French, and they kept the French “sh” pronunciation. These often show up in fashion, food, or cultural words:

Think of it this way: if the word feels a little “fancy” or “French,” your best bet is /ʃ/.

A handful of words don’t pronounce the “ch” at all. The most common one you’ll hear is yacht. Others, like drachm or schism, are rare but worth knowing if you read academic texts.

Here’s the thing: English in real life is not the same as English in textbooks. When native speakers talk quickly, sounds blend together—and that’s when /ʧ/ often pops up unexpectedly.

When a word ending in /t/ is followed by a word starting with /j/ (the “y” sound, like in you or your), the two sounds merge into /ʧ/. This process is called assimilation—basically, your tongue takes a shortcut.

So in fast, natural American English:

And guess what? This isn’t slang or “lazy” speech. Even TV anchors and teachers do it—it’s just how fluent English works.

If you’re listening for the separate /t/ and /j/, you’ll miss what’s really happening in fast speech. That’s why learners often say, “I can read English, but I can’t understand native speakers!” Training your ear for these hidden CH sounds will make listening way easier.

The /ʧ/ sound may seem small, but it’s one of the top troublemakers for English learners. Here are the most common mix-ups I hear as a coach—and how to fix them.

Instead of saying chip, learners say ship. Why? Because /ʧ/ is basically /ʃ/ with a little “t” stop in front—and sometimes the stop disappears.

✅ Fix it: Practice exaggerating the “t” part at the beginning. Say “t…sh…chip” slowly, then speed it up until it blends naturally.

Some learners skip the “sh” part, so chair sounds like tair.

✅ Fix it: Focus on letting the air out in a hiss after the /t/. Think of it as a “noisy t.”

As we covered earlier, voicing is the only difference between cheap and jeep. Learners often forget to “switch the buzz on or off.”

✅ Fix it: Touch your throat while practicing. No buzz = /ʧ/, buzz = /dʒ/.

❤️Coach tip: Remember, even native English-speaking kids usually don’t master /ʧ/ until around age 4 or 5. So if it’s tricky for you, you’re not “bad at English”—you’re just going through the same learning process.

Before you can pronounce CH /ʧ/ confidently, you need to hear it clearly. Many learners think they’re saying /ʧ/ correctly, but if your ear can’t catch the difference between /ʧ/ and nearby sounds, your mouth won’t produce it reliably. That’s why we start with minimal pairs—words that differ by just one sound.

This is the most common confusion. Try these pairs:

Listen carefully: /ʧ/ has that little “t” puff before the “sh.”

Here the mistake is dropping the “sh” part.

Don’t forget the voicing contrast!

The more you practice listening, the more automatic the differences will become—and your pronunciation will follow.

Hearing the CH sound is half the battle—now it’s time to train your mouth. Think of it like exercising a new muscle. Start small, then build up to full, fluent sentences.

Begin with the sound by itself: “ch, ch, ch.”

Then combine /ʧ/ with vowels:

This builds coordination between the stop and the “sh” release.

Practice in all positions:

❤️ Coach tip: Record yourself and compare with native pronunciation. Even tiny differences are easier to catch when you listen back.

Now put the words into short phrases and sentences so the sound feels natural.

Push your speed and clarity with fun tongue twisters:

Don’t worry if you trip up at first—that’s the point! The challenge builds agility and control.

Even though the CH sound is pretty stable in American English, there are a few subtle twists depending on the accent or dialect. Knowing these will make native speech less confusing.

In many Southern varieties, vowels around /ʧ/ may sound a little different. For example, watch or catch might have a more open vowel compared to General American. The /ʧ/ itself doesn’t change much—but the surrounding sounds can make it feel “softer” or “warmer” to the ear.

In AAVE, final consonant clusters are often simplified. That means in a word like lunch (/lʌnʧ/), the /nʧ/ cluster may sometimes be reduced, so it sounds more like lun’. Same with church → chur’. It’s not random—it follows consistent phonological rules.

In very fast, relaxed speech, some native speakers slightly “deaffricate” /ʧ/, making it sound closer to /ʃ/. For instance, watch may sound a bit like wash. This is especially common when people are speaking quickly or blending words together.

❤️ Coach tip: Don’t stress about copying every accent detail. If your goal is clear, neutral American English, stick with the General American version we’ve been practicing. But do train your ear to notice these variations so you’re not thrown off when you hear them.

The CH sound might look small on the page, but as you’ve seen, it carries a lot of weight in real communication. From cheap vs. jeep to watch vs. wash, a tiny slip can totally change the meaning of your words. That’s why mastering it is so powerful—it’s not just about sounding “better,” it’s about being understood clearly and confidently.

Here’s the good news: you already have all the tools you need. You know the mechanics (a quick /t/ + /ʃ/), you know the spelling patterns (ch, tch, tu), you’ve seen how it transforms in connected speech (don’t you → donchu), and you’ve practiced with drills and tongue twisters. Now it’s just about consistency.

Be patient with yourself—remember, even native English-speaking kids usually don’t nail this sound until age 4 or 5. So if it feels tricky, that’s normal. With daily practice (even 5 minutes), your mouth will build the muscle memory, your ear will catch the differences, and your speech will flow more naturally.

So keep going—record yourself, play with minimal pairs, and don’t be afraid to exaggerate while practicing. Step by step, you’ll feel the sound click into place. And one day, you’ll be chatting away and realize… “Hey, I didn’t even think about it—I just said it right.” That’s when you know you’ve mastered it.