Hey there! I’m Emma ❤️ , your American Accent Coach, and today we’re tackling one of the sneakiest sounds in American English: the NG sound, also known as the /ŋ/ sound. You’ve heard it in words like sing, long, thing, and of course in the super common -ing ending (running, playing, talking). At first glance, it might seem easy, just a little “n” at the end of a word, right? But here’s the catch: /ŋ/ isn’t the same as /n/, and it’s definitely not /n/ plus a /g/. It’s its own unique sound, and getting it wrong can make your speech sound unclear or even change the meaning of words.

For one thing, your tongue has to move in a way that’s less obvious than most sounds. It’s made way back in your mouth near the soft palate, not with the tongue tip like /n/. And then there’s the confusing spelling: sometimes <ng> means just /ŋ/ (sing), and sometimes it means /ŋg/ (finger). On top of that, English speakers often drop the full /ŋ/ in casual speech, turning running into runnin’. In this guide, we’ll break down everything you need to know: how to make the NG sound step by step, how to avoid common mistakes, the rules behind /ŋ/ vs. /ŋg/, and even the cultural side of “g-dropping.” By the end, you’ll not only pronounce this sound clearly, you’ll understand how it works and use it confidently in real conversation.

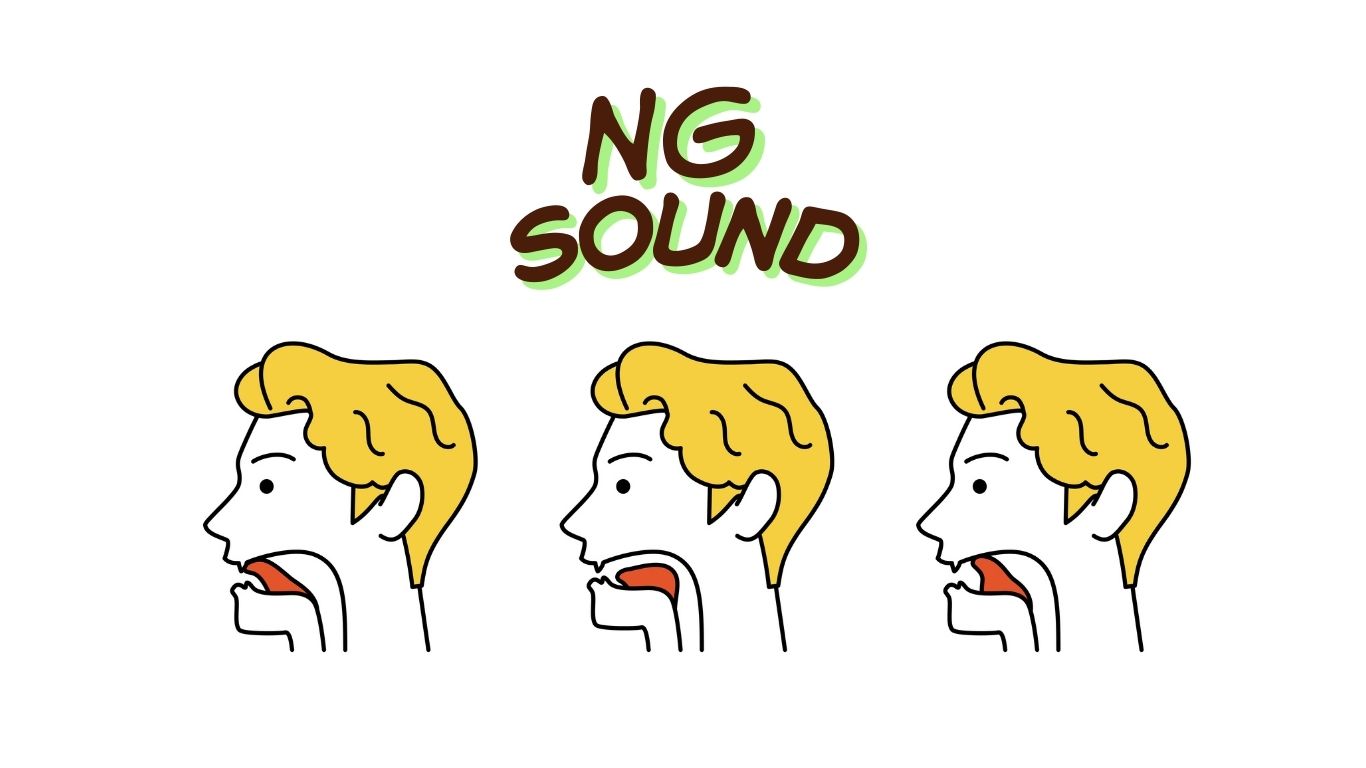

If you want to master any English sound, the first step is understanding exactly how it’s made inside your mouth. The NG sound might look mysterious, but once you know what’s happening with your tongue, throat, and airflow, it becomes much easier to control.

The NG sound is called a voiced velar nasal. That might sound technical, but each word in that label tells you what to do:

Voiced

Your vocal cords vibrate when you make this sound. Try putting your fingers on your throat and saying “nggggg.” Feel that buzzing? That’s voicing. If you don’t feel vibration, you’re probably making it voiceless, which isn’t correct for /ŋ/.

Velar

This part tells us where the sound happens. The back of your tongue presses up against the soft palate (also called the velum). If you trace your tongue from the back of your teeth across the roof of your mouth, you’ll feel it go from hard and bumpy to soft. That soft part is where /ŋ/ lives.

Nasal

This means the air escapes through your nose, not your mouth. When you block the back of your tongue against the velum, the only path left for air is the nasal cavity. If you hold your nose shut while humming “ngggg,” the sound will stop instantly. That’s proof you’re doing it right.

Think of this like a workout routine for your tongue and voice. Follow each step carefully, and repeat them slowly until the movement feels natural.

❤️ Coach’s tip: Think of NG sound as the nasal version of /g/. Same spot, same tongue action, but instead of a burst of air, you let it resonate gently through your nose.

The NG sound doesn’t live alone. It’s part of a little “nasal family” in American English, along with /n/ (as in no) and /m/ (as in me). All three are nasals, which means the airflow escapes through your nose. But the big difference is where in your mouth the blockage happens.

Think of it like three roommates who all live in the same house (your mouth), but in totally different rooms:

If you mix them up, it can completely change the meaning of a word. Saying win instead of wing or sum instead of sung might confuse your listener or make your speech sound less natural.

❌ Common mistake: Many learners replace /ŋ/ with /n/, making thing sound like thin. The key is remembering that your tongue tip must stay relaxed and forward for NG sound.

Minimal pairs to practice:

These two are easier to tell apart because one is a lip sound and the other is a tongue sound.

Minimal pairs to practice:

Instead of just listening, focus on what you feel:

Here’s a simple chart to help you see the differences at a glance:

| Sound | Place of Articulation (Where?) | What Moves? | Example Words | Key Feeling |

| /m/ (bilabial nasal) | Lips pressed together | Lower lip | me, sum, hammer | Buzzing in the lips |

| /n/ (alveolar nasal) | Tongue tip against alveolar ridge (behind top teeth) | Tongue tip | no, sun, dinner | Pressure at the front of the mouth |

| /ŋ/ (velar nasal) | Back of tongue against soft palate | Back of tongue | sing, long, bring | Deep closure in the back of the mouth, nasal hum |

Every sound in English has “rules” about where it can appear in a word. For /ŋ/, the rules are especially strict. Understanding them will help you predict pronunciation and avoid errors.

In American English, words never start with the NG sound. You’ll never find a native English word that begins with ng. If you see spellings like gnat or knight, the /g/ or /k/ is silent, and the word actually starts with /n/.

In English, NG sound always comes in the middle or at the end of a syllable.

Even in the middle of a word, /ŋ/ still closes a syllable. For example: singer is divided as sing-er (/ˈsɪŋ.ər/), not si-nger.

It’s not because it’s hard to pronounce. Many languages use it at the start of words with no problem. In English, it’s simply a historical accident. The sound NG used to be just a variant of /n/ in Old English, and it never developed at the beginning of words. Over time, English kept that rule.

If you’ve ever looked at English spelling and wondered, “Why does sing sound different from finger?” you’re not alone. The /ŋ/ sound is one of the trickiest when it comes to spelling because the letters don’t always match up with the sound you expect. Let’s break it down.

The most common spelling is the letter combination ng. When you see this at the end of a word or syllable, it usually represents the single /ŋ/ sound.

Examples:

When the letter n comes before a k or g sound, the /n/ changes into /ŋ/. This is called assimilation—your tongue anticipates the upcoming velar sound and moves to the back of the mouth early.

Examples:

So in bank, the “n” is not /n/. It’s /ŋ/ + /k/: /bæŋk/.

The -ing suffix is everywhere in English: it marks progressive verbs (running), gerunds (swimming), and adjectives (interesting). No matter what the word is, this suffix is always pronounced /ɪŋ/, not /ɪn/ or /ɪŋg/.

Examples:

It might feel like random spelling, but there’s logic behind it. When your tongue has to make two movements in a row (from the front for /n/ to the back for /k/ or /g/), it takes extra effort. So English simplifies the motion by just moving the tongue to the back early. That’s why bank is /bæŋk/ instead of /bænk/. It’s faster and smoother.

So you’ve learned that <ng> often spells /ŋ/. But wait—why does singer sound different from finger? This is one of the most confusing areas for English learners, because sometimes <ng> means just /ŋ/, and sometimes it means /ŋg/. Luckily, there’s a pattern you can follow.

If <ng> comes at the end of a word or the end of a root word, you only pronounce /ŋ/. No hard /g/.

Examples:

If <ng> is part of the root word (not just a suffix), then the /g/ is pronounced too.

Examples:

There’s one special exception learners must memorize. When a one-syllable adjective ending in <ng> takes the comparative -er or superlative -est, the /g/ comes back.

Even though the base word ends in /ŋ/, adding these particular suffixes changes the pronunciation to /ŋg/.

Here’s a fun twist: English has two -er endings that look the same but act differently.

So the key is grammar: one -er makes a person (singer), the other makes a comparison (longer).

Try these to sharpen your ear:

Mastering NG sound in single words is a big step, but real English is spoken in phrases and sentences, not word lists. That’s where connected speech comes in. Native speakers don’t pronounce every sound slowly and clearly—they link, reduce, and sometimes drop sounds altogether. And the /ŋ/ sound plays a big role in these changes.

One of the most common features of connected American English is “g-dropping.” You’ve probably heard runnin’, talkin’, or goin’ instead of the full running, talking, going. This isn’t a mistake. It’s simply the alveolar /n/ replacing the velar /ŋ/ in casual, quick speech.

When a word ending in /ŋ/ is followed by a vowel, native speakers often let the nasal flow directly into the next word without a break.

Notice how the nasal sound blends smoothly, sometimes creating a little extra glide (like a /w/) to connect the sounds.

In rapid speech, /ŋ/ often gets shortened or blurred, especially in high-frequency phrases.

Here, the NG sound in going usually reduces to /n/, making the whole phrase smoother.

Try reading these aloud first slowly, then more quickly. Listen for how the /ŋ/ either holds steady or shifts into /n/.

Even after understanding the rules, many learners run into the same pronunciation traps. Let’s go through the most frequent ones and how to fix them.

❌ Saying sing-guh instead of sing.

This happens because learners see the letter g and want to pronounce it. But remember: if <ng> is at the end of a root word (sing, long, king), the correct sound is just NG, no /g/.

✅ Fix it: Hold the /ŋ/ like a hum: ngggg. Don’t release it. Practice sing, ring, bring slowly, focusing on ending with the nasal hum only.

❌ Saying thin instead of thing, or win instead of wing.

This happens when the tongue tip lifts instead of the back of the tongue.

✅ Fix it: Keep your tongue tip relaxed behind your lower teeth. Think of making a /g/ sound, but don’t release it. Practice minimal pairs: thin–thing, win–wing, ran–rang.

❌ Saying run-in instead of running.

Sometimes learners reduce the sound too much, especially when speaking quickly, and the nasal disappears.

✅ Fix it: Slow down and exaggerate the ending: run-NING, sin-GING, bring-ING. Over-practice clearly, then speed up.

❌ Making the NG sound too long or too nasal, almost like humming through your nose unnaturally.

Learners sometimes overcompensate by holding the sound too much.

✅ Fix it: Keep it short and natural. Practice with the -ing ending in everyday verbs: walking, talking, cooking. Record yourself and compare to native speakers—your /ŋ/ should sound smooth, not exaggerated.

Quick reminder: /ŋ/ is a single, clean sound, not /n/, not /ngg/, and not a nasal hum that goes on forever. Think of it as the nasal cousin of /g/—short, neat, and controlled.

Monday – Isolation and Awareness

Tuesday – Minimal Pairs

Wednesday – Word Lists

Thursday – Sentences

Friday – Connected Speech

Weekend – Review & Fun Practice

The NG sound may be small, but it carries a lot of weight in American English. It shows up in thousands of everyday words, from sing and long to the ever-present -ing ending. At first, it might feel awkward—your tongue is working in a new spot, the spelling looks confusing, and you’re tempted to add a /g/ or swap it with /n/. But once you really “get it,” this sound becomes second nature.

Here’s the big picture: /ŋ/ is the nasal cousin of /g/. Same tongue position, but with air flowing through the nose. It never starts a word in English, but it’s everywhere else, especially in verbs, gerunds, and participles. Learn the difference between /ŋ/ and /ŋg/, tune your ear to both -ing and -in’, and you’ll sound far more natural and confident in conversation.

Most importantly, don’t stress if it feels tricky at first. Even native kids need years to master it. With the drills, word lists, and practice sentences in this guide, you can train your tongue and your ear step by step. Record yourself, practice in short bursts every day, and celebrate small wins along the way. Bit by bit, you’ll transform /ŋ/ from a “mystery sound” into a tool you use automatically.

So the next time you’re speaking, whether you’re singing, laughing, bringing, or learning, you’ll know exactly how to nail that final “ng.” Keep practicing, trust the process, and you’ll hear yourself sounding clearer, smoother, and more like a natural American English speaker ❤️.