Hey there! I’m Emma, your American Accent Coach, and today we’re exploring a sound that feels both comforting and deceptively simple: the American M sound. Think about it: /m/ is often one of the very first sounds humans ever make. Babies around the world babble “mama” long before they can say much else. It’s soft, warm, and familiar. And since nearly every language has some version of this sound, most learners feel pretty confident about it. But here’s the twist: in American English, the /m/ isn’t always as straightforward as it seems.

In this guide, we’ll break it all down step by step: how to make the M sound correctly, how it shows up in spelling, the mistakes learners make (and how to fix them), and how to practice it until it feels second nature. By the end, you’ll have the tools to make your /m/ sound clear, confident, and truly American.

The M sound may feel simple, but it plays a big role in how clear and natural your English sounds. It appears in countless everyday words like me, my, more, and time, and makes up nearly 3% of spoken English. If your lips don’t close fully, if your voicing is weak, or if your first language influences the way you say it, the /m/ can sound unclear or even disappear. Mastering it helps you build a solid foundation for your accent, ensuring that your speech is understood easily and sounds confident.

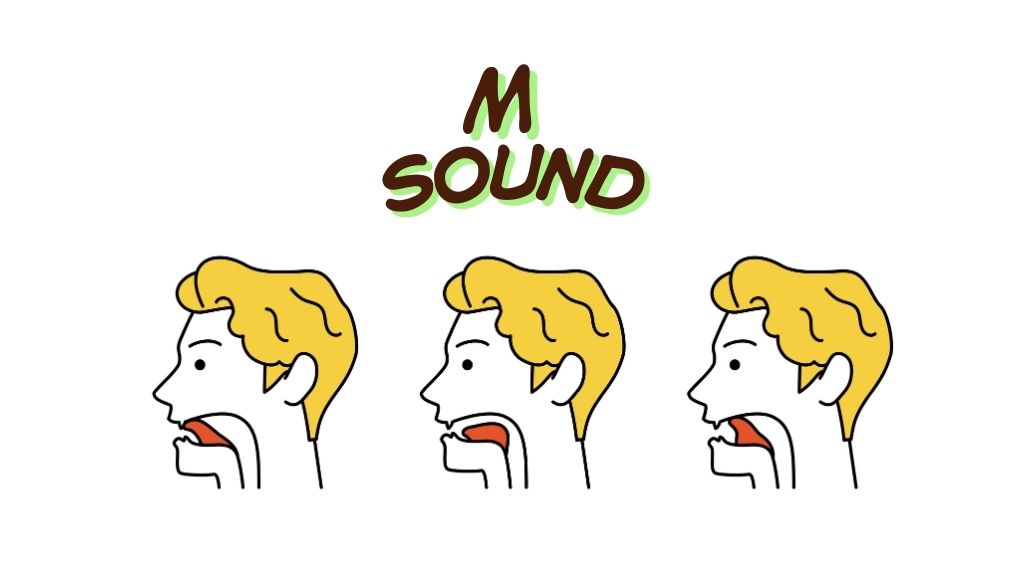

The M sound is often called the “humming sound”, and once you practice it, you’ll understand why. It’s voiced, it resonates through your nose, and it has a warm, steady quality. To get it right, you need to coordinate your lips, your voice, and your airflow. Let’s break it down step by step:

Quick self-checks:

✨ Pro tip: Think of M sound as a “nasal vowel” with your lips closed. If it feels smooth, steady, and buzzing, you’re on the right track.

Luckily, the /m/ sound in English is spelled quite consistently compared to other sounds. Most of the time, it’s simply written with the letter m, as in man, mother, moon, or time. Double mm also represents the same sound, like in summer or common.

There are, however, some trickier spellings that learners often stumble on. For example, when you see mb at the end of a word, the b is silent: thumb, climb, lamb, comb, bomb. The same thing happens with mn at the end of some words, where the n is silent: autumn, column, hymn.

Another small group of words uses lm, where the l disappears and only the /m/ is heard: calm, palm, balm. And finally, sometimes the spelling me represents a final M sound after a long vowel, like in time, home, or same.

✨ The key takeaway: English spelling can be quirky, but when it comes to /m/, once you know these few patterns, you’ll recognize it almost every time.

The M sound doesn’t live alone in English. It has two “siblings,” /n/ (as in no) and /ŋ/ (as in sing). All three are nasal consonants, which means the air flows out through the nose. They’re also all voiced, so your vocal cords vibrate for each one. The difference lies in where you block the air in your mouth.

A quick way to feel the difference is to say these words slowly: sum – sun – sung. Notice how the part of your mouth that blocks the air changes each time.

Practice tip: Work with minimal pairs like map/nap, hum/hung, gum/gun. These drills train both your ear (to hear the difference) and your mouth (to produce the difference).

✨ Remember: the only thing that separates these nasal siblings is place of articulation. Once you know where to block the airflow, the rest is the same.

Even if you don’t see someone’s lips, you can usually hear when they are making the M sound. That’s because it has a very distinct “humming” quality. The sound is steady, low, and resonant, almost like a soft background note.

When you say /m/, your lips close completely, your voice turns on, and the air flows through your nose. This combination creates a smooth, buzzing sound that listeners instantly recognize. It’s also why words with /m/ often feel warm and comforting, like mom, home, or mmm when you taste something delicious.

What really sets /m/ apart from its nasal siblings is how it transitions into nearby vowels. After /m/, the vowel often feels like it “rises” smoothly, while after /n/ or /ŋ/ the vowel starts from a different tongue position. Native speakers pick up on these subtle transitions automatically, so practicing them clearly helps your M sound natural and distinct.

Quick exercise: Say me, may, my, moo. Focus on how your lips release from the closed position into the vowel. That little release is what makes the /m/ so recognizable to the ear.

Even though /m/ feels easy, learners often run into a few predictable problems. Here are the ones I hear most often as a coach:

When we speak naturally, words flow together, and the /m/ sound often changes slightly depending on its neighbors. Two processes are especially important: assimilation and nasalization.

This isn’t sloppy English, it’s how native speakers make speech smoother and faster.

Takeaway: Don’t fight these natural changes. If you try to over-pronounce every /m/, your speech may sound robotic. Instead, listen closely to how native speakers let sounds blend and practice shadowing them.

The /m/ itself is one of the most stable sounds in American English. No matter where you go in the U.S., people make it by closing their lips and letting the sound hum through the nose. But what does change is the vowel that comes right before it, and this is where regional accents really stand out.

Takeaway: You don’t need to copy these regional variations unless you want to. But being aware of them will make it much easier to understand people from different parts of the U.S.

The /m/ sound does more than just help form words. It also plays an important part in how English builds meaning and expresses ideas.

Takeaway: The /m/ isn’t just common — it’s symbolic. Mastering it gives you both clearer pronunciation and access to some of the most natural, human sounds in English.

The best way to master /m/ is with consistent, focused practice. Start simple, then build up to real conversation. Here’s a step-by-step routine you can use:

Pro tip: Record yourself and compare with a native speaker. Apps like ChatterFox can give you feedback and show you where you’re drifting off.

The M sound may seem simple, but it’s one of the pillars of clear, natural American English. By closing your lips fully, engaging your voice, and letting the air flow smoothly through your nose, you create that steady, familiar hum that makes words like me, mom, time, and home sound complete and easy to understand.

Remember, it’s not just about making the sound in isolation. Pay attention to how /m/ connects to nearby vowels, how it shows up in everyday spelling patterns, and how native speakers use it in fast, connected speech. Keep practicing with syllables, words, and minimal pairs, and don’t forget to record yourself to catch small slips.

Most importantly, give yourself patience. Even native speakers fine-tune their /m/ through years of natural practice. With steady effort, your /m/ will become second nature too, helping your accent sound clearer, smoother, and more confident in every conversation.